Sorry Not Sorry

July 31, 2024

As Canada’s dronegate scandal continues to unfold, we are being subjected to the usual “apologies.”

In case you missed it, Spygate got underway even before the River Seine did its part to dazzle us with the Opening Ceremonies on July 26.

On Monday, July 22, staff members of the New Zealand women’s soccer team noticed a drone flying over their practice in Saint-Étienne. They informed the police who promptly tracked the drone to one Joseph Lombardi, a 43-year-old analyst with the Canadian women’s soccer team. Police searched his hotel room and seized his drone. Lombardi admitted that he had indeed used the drone to obtain footage of New Zealand’s practice sessions and that the videos “had enabled him to learn the tactics of the opposing team.”

Lombardi was charged with flying an unmanned aircraft over a prohibited area, given an 8-month suspended sentence, and sent home. Assistant coach Jasmine Mander was also sent home (but not charged), as was Head Coach Bev Priestman, a few days later. Since then, FIFA, soccer’s governing body, has banned Priestman from coaching for one year.

There’s more—new details about who knew what and when seem to be emerging daily—but for our purposes, I want to focus on the initial statement Bev Priestman issued through her lawyers on July 28. Here’s some of what she said:

"I am absolutely heartbroken for the players, and I would like to apologize from the bottom of my heart for the impact this situation has had on all of them.”

“As the leader of the team on the field, I want to take accountability, and I plan to fully cooperate with the investigation.”

“To Canada, I am sorry. You have been my home and a country I have fallen in love with. I hope you will continue to support these extremely talented and hardworking players, to help them defy all odds and show their true character.”

(Read the full statement.)

I don’t know about you, but that statement strikes me as a half-apology, at best.

Granted Priestman says she is refraining from saying more because of the appeals process and ongoing investigation, but notice she only says she “wants to take accountability,” not that she actually does. (By the way, I think she wanted the word “responsibility,” but that’s another matter.)

Instead of coming clean and fessing up to her role in the scandal—or even for being willfully blind (if she was…)—she instead apologizes for the “impact on the players” and says she is “heartbroken for them.”

She does say, “To Canada, I am sorry”—but it's far from clear what exactly she's sorry for.

This is not the only recent soccer sorry.

In other news, Argentina’s Enzo Fernández was forced to apologize for chanting racist remarks against French national players of African heritage during his team’s Copa América celebrations.

"That video, that moment, those words do not reflect my beliefs or my character,” Fernández said.

(Really? If someone’s words and actions don’t reflect their character, what do they reflect?)

And this: "I … apologize for getting caught up in the euphoria of our Copa América celebrations.”

(Sure, we understand, Enzo. Anyone can see how easy it is to go from celebrating your team’s win in a major tournament one minute to making racist chants the next.)

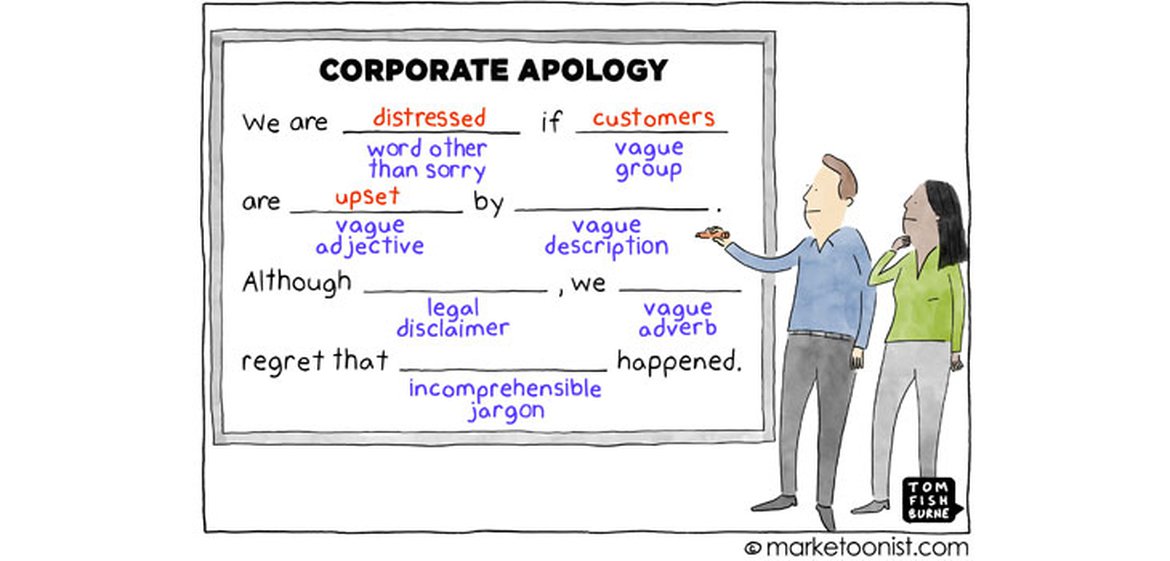

Sadly, half-apologies aren’t restricted to the world of international soccer. They show up in the corporate world too. With alarming frequency, in fact.

Take this recent example. On July 25, Galen Weston, Chairman of Loblaw and Chairman and Chief Executive Officer of George Weston Group of Companies announced a settlement of the class action lawsuits regarding bread price fixing. This was his apology, in part:

“On behalf of the Weston group of companies, we are sorry for the price-fixing behaviour we discovered and self-reported in 2015. This behaviour should never have happened.”

Notice the convenient use of the passive voice? “This behaviour should never have happened.” As if the behaviour somehow fell from the sky. Sorry Mr. Weston, but as leader of your organizations, you should have owned the behaviour: “We were wrong to behave that way” would have been more like it.

None of these so-called apologies have any chance of being cited as models by “sorrywatchers” Susan McCarthy and Marjorie Ingall.

On their website, Sorrywatch.com, the duo shares The Six Steps to a Good Apology:

- Use the words, “I’m sorry” or “I apologize.” “Regret” is not an apology.

- Say specifically what you’re sorry FOR. (One of Priestman’s omissions.)

- Show you understand why the thing you said or did was BAD. (Another omission from Priestman.)

- Be very careful if you want to provide explanation; don’t let it slide into excuse. (As Fernández did.)

- Explain the actions you’re taking to ensure this won’t happen again.

- Can you make reparations? Make reparations.

While all six steps are important, McCarthy and Ingall say they’re not created equal. In summarizing a 2016 academic research paper titled “An Exploration of the Structure of Effective Apologies,” they say, “the researchers found that the most important, by far, was acknowledgment of responsibility.”

It should come as no surprise that this step is the one people have the most trouble with. Here's what McCarthy and Ingall say:

“Most of us don’t like to take ownership of a screw-up because to do so often conflicts with our self-image as a good person. Consciously or not, we want there to be extenuating circumstances, or we want the other person to be responsible for triggering our bad behavior. We loathe saying ‘I screwed up; I own that’ because we loathe believing it.”

I recognize that some of the blame for the sorry state (no pun intended!) of today's public apologies should fall on the shoulders of lawyers and crisis managers. They are often the ones responsible for crafting a murky message to avoid or limit liability down the road.

But, oh, how I would love to see more genuine apologies.

Over and over, history has shown us that if you’re caught messing up, you’ll inevitably pay for it at some point. I can’t help feeling it would be better to admit your wrongdoing now and get on with the rest of your life. Otherwise you’ll likely find yourself, in the words of the immortal Ricky Ricardo, doing a whole lot of “splainin.”

Remember this: A good apology should be “plain.” Admit your offence, say you’re sorry, clearly acknowledge the impact your offence has had on others, and do what you can to make good—now and in the future.

Effective Communication | Writing Tips & Tools | Plain Language