Duct Tape To The Rescue

Oct. 19, 2018

The day before heading off to Peru, I made the last of many trips to my local Mountain Equipment Co-Op to buy an essential piece of gear – trekking poles.

I was pretty stoked by those poles. Aside from making me feel like a real hiker, they boasted all kinds of fancy-sounding and important-seeming qualities: lightweight, EVA grips; breathable, moisture-wicking straps; and interchangeable, non-scarring rubber “Tech Tips.”

But the thing that really got me excited was the fact that my new poles were made of three inter-connected sections that folded “Z-style” for easy packing.

Just the ticket, I thought! I could take the poles apart and stash them handily almost anywhere in my luggage. On the trek, I would simply reassemble them and merrily hike away, safe in the knowledge that the “SlideLock technology” and “durable FlickLock Pro adjustments clamp” would keep the contraptions secure.

How wrong I was.

On Day 2, on our climb up to Lake Humantay, I found myself battling with my “beloved” poles. They kept coming apart. Spontaneously. I’d plant a pole, and somehow the bottom third would stick in the ground, the middle third would dangle, and I would be flailing, the pole and I essentially having parted company.

Maybe I was doing something wrong. Maybe it was a design flaw. I don’t know.

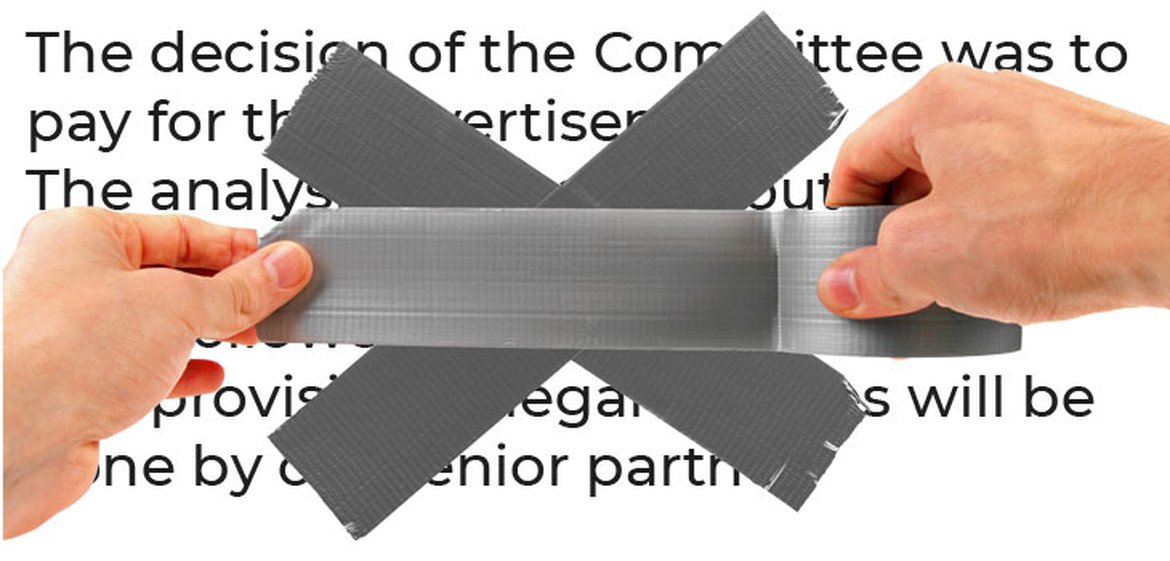

What I do know is that the concept that looked so good – collapsible poles! – was, in practice, not so good. I ended up having to put duct tape on all the joints to keep the poles together, thereby rendering null and void the very folding quality that I’d been so enamored of.

The same thing could be said about today’s topic – nominalizations. On first glance, they might look pretty good. But in practice? Well, I’d say most could use a little duct tape.

What the heck are nominalizations, you ask? Nominalizations are simply nouns created from another part of speech – either verbs or adjectives.

Here are three examples:

- The decision of the Committee was to pay for the advertisement.

- The analysis was carried out in September and the development of the plan followed in October.

- The provision of legal services will be done by our senior partner.

In each example, the writers (who shall remain nameless) made a noun (a person or a thing) out of a verb (an action word).

In fairness to all the engineers, lawyers, and other consultants out there, I will admit that you come by the tendency to use nominalizations honestly. You are trained to think about activities – such as investigating, analyzing, measuring, drafting, evaluating, and recommending – as static, abstract concepts. So, it seems perfectly natural to say, “the investigation,” “the analysis” or “the recommendation.”

Also, professionals tend to want to step aside and let their work speak for itself. This is especially true when they are writing reports.

While nominalizations are not technically wrong, in my view, they should be firmly and not-so-politely shown the door.

Why? Nominalizations result in sentences that are harder to read because they are longer and more awkward than they need to be. They also result in sentences that are potentially vague since they give priority to the action rather the people responsible. (Remember the old “Mistakes were made”?)

To inject energy and clarity into the three examples above, we need to go back to Grammar 101 and recall that the two most basic units of a sentence are the subject and the verb. The subject is the actor; the verb is the action. The subject, a person or a thing, should be doing something.

So, rewrites might look like this:

- The Committee decided to pay for the advertisement.

- We analyzed the data in September and developed the plan in October.

- Our senior partner will provide the legal services.

And remember, it’s not just verbs that seem intent on crossing over to the dark side. Adjectives can occasionally go rogue too.

For example:

- The applicability of the scoring chart will be determined.

- The slowness of the company to adopt the new policy was a problem.

In these examples, applicability is a noun made from the adjective applicable, while slowness is a noun made from the adjective slow.

To rid the sentences of the nominalizations, try these instead:

- We will determine if the scoring chart is applicable.

- The company was slow to adopt the new policy.

If you’re wondering if it’s ever okay to use nominalizations, the answer is yes – if we don’t know who is responsible for the action, or responsibility is irrelevant.

But still...you shouldn’t use them too often. If you do, be prepared to face me and my big roll of duct tape. Forewarned is forearmed.

Words